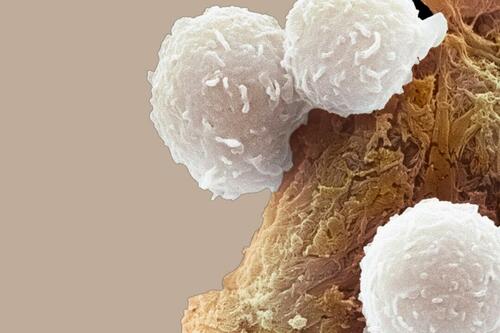

Раковые клетки «сотрудничают», чтобы выжить

Автор: Джордж Цитронер, The Epoch Times (подчеркнуто нами),

Ученые обнаружили, что Раковые клетки, которые долгое время считались конкурентоспособными друг с другом, на самом деле работают вместе, чтобы получить питательные вещества в суровых условиях.Согласно новому исследованию.

Mihiripix/Shutterstock

Mihiripix/ShutterstockИсследователи из Нью-Йоркского университета определили специфический фермент, который позволяет этому сотрудничеству, позволяя опухолевым клеткам делиться ресурсами, когда питательных веществ мало. Когда этот фермент был заблокирован, раковые клетки не могли питаться и полностью умирали.

Сотрудничество в суровых условиях

Недавние исследования, опубликованные в Nature, подчеркивают интригующий аспект биологии рака: Хотя раковые клетки исторически рассматривались как конкуренты для питательных веществ и ресурсов, они также могут проявлять совместное поведение.Особенно в сложных условиях. Исследователи изучили эту двойственность у мышей и проиллюстрировали сотрудничество между организмами в экстремальных условиях.

Например, исследователи отметили, что микроорганизмы, такие как дрожжи, работают вместе, чтобы найти питательные вещества, но только когда сталкиваются с голодом. Точно так же раковые клетки, которые нуждаются в питательных веществах для процветания и размножения в опасных для жизни опухолях, часто живут в средах, где питательных веществ мало. "Хотя конкуренция, безусловно, имеет решающее значение для эволюции опухоли и прогрессирования рака, кооперативные взаимодействия внутри опухолей также важны, хотя и плохо изучены.- отметили исследователи.

Они отметили, что дефицит питательных веществ является определяющей чертой микросреды опухоли и предположили, что естественный отбор может быть механизмом, который поощряет выживание раковых клеток, которые могут сотрудничать с источником питательных веществ.

Голодные раковые клетки работают вместе для выживания

Чтобы выяснить, взаимодействуют ли раковые клетки, исследователи отслеживали рост клеток из разных типов опухолей.

Они отметили, что В то время как раковые клетки обычно поглощают аминокислоты, строительные блоки белков, конкурентно, голодая раковые клетки аминокислоты глутамина.Самая распространенная аминокислота в организме, привела их к сотрудничеству в приобретении необходимых ресурсов.

«Удивительно, но мы заметили, что Ограничение аминокислот принесло пользу более крупным клеточным популяциям«Но не редкие, предполагая, что это совместный процесс, который зависит от плотности населения», - сказал Карлос Кармона-Фонтейн, доцент биологии в Нью-Йоркском университете и старший автор. «Стало совершенно ясно, что между опухолевыми клетками существует подлинное сотрудничество. "

Проводя дополнительные эксперименты с клетками рака кожи, молочной железы и легких, исследователи определили, что ключевым источником питательных веществ для раковых клеток являются олигопептиды, которые представляют собой кусочки небольших аминокислот, которые действуют как посредники между клетками.

Решающий фермент может быть нацелен на убийство рака

Вместо того, чтобы просто принимать пептиды, которые представляют собой небольшие белки, раковые клетки становятся кооперативными. Они выпускают специальный фермент под названием CNDP2, который разбивает эти пептиды на еще более мелкие кусочки, свободные аминокислоты, которые они затем могут легко использовать для получения энергии.

"Поскольку этот процесс происходит вне клеток, результатом является общий пул аминокислот, который становится общим благом для рака.- отметил он.

Когда Бестатин, препарат, который ингибирует функцию CNDP2, был применен к раковым клеткам, они стали неспособны питаться небольшими аминокислотами и полностью отмирали.

Бестатин, также известный как убенимекс, не одобрен для какого-либо лечения в Европе или Соединенных Штатах, сказала Марианна Мацо, сертифицированная продвинутая геронтологическая медсестра-практик с магистром и докторской степенью в области геронтологии и сертификатами в качестве паллиативной помощи, геронтологии и онкологии продвинутая медсестра-практик. Но он одобрен и используется в Японии более 35 лет в качестве вспомогательной терапии после химиотерапии.

Адъювантное лечение — это препараты, которые используются в дополнение к первичной терапии для повышения эффективности начальной терапии. "В Японии он используется для поддержания ремиссии и выживания при остром нелимфоцитарном лейкозе у взрослых пациентовs», — отметил Матцо.

Бестатин последовательно блокировал поглощение олигопептида во всех линиях раковых клеток, протестированных in vitro, которые включали в себя широкий спектр клеток кожи, легких, молочной железы, толстой кишки и опухоли поджелудочной железы.

Ученые заблокировали ген для голодания опухолевых клеток

Определив CNDP2 как фактор, лежащий в основе совместного процесса питания в раковых клетках, ученые продолжили тестировать, что происходит, когда фермент отсутствует, используя технологию редактирования генов CRISPR, чтобы выбить ген CNDP2 в опухолевых клетках.

Они обнаружили, что Рост опухоли, удаленной геном, был снижен, разница еще более выражена, когда удаление CNDP2 сочеталось с ограничением доступа опухоли к аминокислотам с использованием диет с низким содержанием олигопептидов.. Диетические источники олигопептидов включают такие продукты, как молоко, яйца, мясо, соя, бобы, зерна и семена, такие как конопля и льняное семя.

Исследователи также смогли уменьшить рост опухолей, которые не были удалены CNDP2, объединив эти диеты с бестатином, комбинацией, которая могла бы помочь пациентам под клинической помощью.

«Поскольку мы убрали их способность секретировать фермент и использовать олигопептиды в их среде, клетки без CNDP2 больше не могут сотрудничать, что предотвращает рост опухоли», — сказал Кармона-Фонтейн. «Мы надеемся, что более четкое понимание этого механизма поможет нам сделать наркотики более целенаправленными и эффективными. "

Последствия и будущие исследования

Исследователи стремятся перевести эти результаты в методы лечения рака, которые нарушают клеточное сотрудничество. Хотя это раннее исследование на мышах является доказательством концепции, эффективность у людей требует дальнейшего изучения.

Существующие методы лечения рака работают путем физического удаления рака хирургическим путем, уничтожения клеток с помощью радиации или химиотерапии, повышения защиты организма с помощью иммунотерапии или изменения того, как клетки растут с помощью целевой терапии. Тем не менее, результаты звучат «перспективно» и предлагают другой подход к лечению рака.

"Эта модель стремится заморить раковые клетки голодом до смерти, что является новым подходом к лечению рака."

Тайлер Дерден

Мон, 03/03/2025 - 19:15

![Budowa dużego sklepu meblowego na Nowym Mieście w Rzeszowie [ZDJĘCIA]](https://storage.googleapis.com/bieszczady/rzeszow24/articles/image/e4bcfd4f-47cd-42d9-b865-7c5ee3ad1bbf)